This is one of the great articles found in the Tenkara Magazine we recently published. The article was written by Jason Klass, illustrations done by Anthony Naples. Unfortunately we missed a small portion of the article, specifically between technique #4 and #5. So, here is the complete article, which we hope you’ll enjoy and will give you a small flavor for the content in the first magazine devoted to tenkara in the world.

Ten Techniques for Tenkara

One thing beginning anglers often find daunting and mysterious is what to do once they set foot on the stream. They may have confidence that they bought good gear, but how do you actually present the fly effectively?

In this article, I will cover just a few presentation techniques that work well with tenkara. Some are Japanese in origin while others are western (and some are both), but all have been proven highly effective. Learning them can go a long way toward advancing a beginner to a highly skilled angler.

1. The Upstream Dead Drift

The dead drift is probably the most widely used presentation when fishing for trout. And for good reason. A trout’s main diet is aquatic insects. Insects are small, stream currents are strong. Once swept out from beneath a rock or dislodged from the streambed, a tiny insect is pretty much at the mercy of the current. They often drift along at the same speed of the flow (hence the name “dead” drift) until they’re lucky enough to regain their footing or unlucky enough to wind up in the mouth of a hungry trout.

From a trout’s perspective, this is an ideal feeding situation. All it has to do is find a place to hold (in a pool, behind a rock, etc.) and wait for the insects to drift to it like a pizza delivery. It’s not only ideal because of the sheer amount of insects trout get exposed to, but also because it requires minimal effort. Unlike chasing a swimming insect (which they may or may not catch) trout can easily scoop up a dead-drifting nymph or larva with a simple turn of the head or slight lateral move with very little energy expenditure.

So since this is the ideal feeding situation for trout, it’s no wonder the dead drift is such a highly effective and universal presentation. The key to a good dead drift presentation is to allow the fly to flow at the exact same speed as the current. If it “drags” from currents or from pulling the line, it could look unnatural and will be refused by the fish. Luckily, the long length of tenkara rods and their light lines are highly effective at getting a good dead drift. Tenkara rods allow you to keep only the fly and tippet in the water (and the line out of it). This reduces the chances of the current pulling the line and creating unnatural drag on the fly.

Fishing upstream is probably the first presentation that most fly anglers learn and is the easiest to master. You simply cast your fly directly upstream and let it flow back towards you. As it does, it will create slack line that you’ll need to compensate for in order to keep the line tight and out of the water. Keep your rod high and slowly raise it to keep the line taut as it comes back to you. Just make sure you don’t raise it too high or you’ll create drag.

Because trout face upstream, there’s little chance they will be able to see you since you’ll be standing behind them, out of their cone of vision. So this presentation is very stealthy. However, it’s pretty common for the tippet to come down before the fly, making it look suspicious. If you’re fishing to spooky or highly pressured trout, this might not be the best presentation since they can potentially see the tippet before the fly.

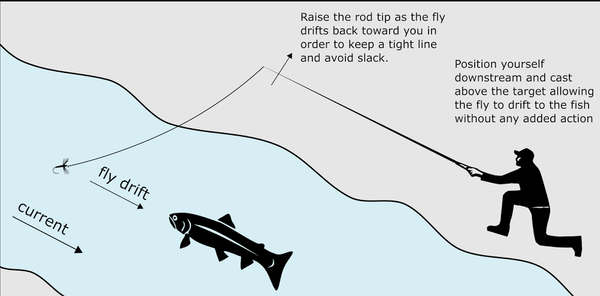

2. The Downstream Dead Drift

In order to guarantee that the fly (rather than your tippet or line) is the first thing the fish sees, you can make the same dead drift presentation downstream. You might also be in a situation where it’s not possible to cast upstream (because of trees, etc.) and downstream is your only option.

It’s basically the same as the upstream presentation except in reverse. You’ll make a short cast closer to where you’re standing, keep the rod high, and slowly lower the rod at the same speed as the current to avoid any drag on the fly. When you’ve reached the end of the drift (i.e. there is no more line to feed out), pick it up and cast again.

Since fish face upstream, you’re directly in their cone of vision if you’re fishing the downstream dead drift. If you’re far enough away, though, you’re probably okay. But you can also kneel to maintain a low profile, wear camouflage, or hide behind an obstruction to avoid being seen.

One nice advantage of this presentation is that the fish will see your fly first, reducing the chances that they’ll be spooked by your tippet or line.

3. Pulsing the Fly

Above, I said that insects are at the mercy of the current. But this isn’t 100 percent true 100 percent of the time. In fact, some insects are quite good swimmers and their pulsing motion as they move through the water column can trigger aggressive instinctual strikes from fish, which want to catch the insect before it escapes (or is caught by another trout).

In this presentation, you’re essentially mimicking the swimming motion of insects and small crustaceans. You cast out the same way you would with the dead drift presentations above, let the fly sink a little, then very gently start twitching the rod as you follow the drift. This makes the fly “swim” underwater, making it look alive.

This technique is very easy, but also very easy to botch. The key is to be subtle. You don’t want to move the rod too much. When done correctly, an observer wouldn’t even notice you’re moving the rod. The fly should only be moving about one to three inches (not 12 inches). If you move the fly too much it not only looks unnatural, but it makes it too difficult for the fish to catch. You want to offer them an enticing but easy meal.

The frequency of the pulse also matters. Sometimes, twitching the rod once every two seconds will work and sometimes twitching it twice every second will work. There is no rule here. You just have to experiment with different frequencies to figure out what will work. And keep in mind that it can change day to day (even on the same stream).

Tip: this presentation is most effective when used with a fly design that has “moving parts.” Classic soft hackle wet flies work, but because their hackle is swept back over the body of the hook, the motion is limited. I prefer the forward-facing hackle of the traditional sakasa kebari, which opens and closes when pulsed, creating a very lifelike movement.

This presentation can be fished upstream, downstream and cross-stream, making it very versatile. It’s a good choice as a prospecting technique, or when you’re caught in a hatch of insects that actively swim to the surface to emerge.

Just bear in mind that because you’re moving the fly, you’re making it a little more difficult for the trout to catch. This can result in more missed strikes or bad hook-sets. But if you follow the advice above and keep the movement subtle, this shouldn’t be an issue.

4. The Swing

This presentation is a favorite among wet fly anglers. It’s a simple downstream presentation where you let the fly “sweep” down and across the stream.

Unlike the dead drift, in this technique, drag is favorable and you actually do want more of your line in the water to leverage the current to move the fly.

Facing perpendicular to the stream, cast slightly up and across stream. Allow the fly to drift just downstream of you as you follow the line with your rod (the same way you would in the dead drift presentation). Then, stop the rod. Let the current drag the line and sweep the fly across the stream diagonally until it completely straightens out. When that happens, pick up for the next cast.

The swing mimics swimming insects well (especially caddis pupae) and it covers a lot of water so it’s also good searching technique. But like the pulse, you can miss a lot of strikes if you move it too fast, so it’s better to err on the side of swinging the fly too slowly. And when you do get a strike, hold on! Fish often hit swinging flies with all they’ve got.

5. The Leisenring Lift

The Leisenring Lift is like a variation of the swing—except instead of the fly moving down and across stream, it’s moving from the stream bottom up to the surface.

The original technique involved using weighted flies or split shot to get the fly down as deep as possible. But you can also achieve the same goal by modifying this presentation and combining it with another tenkara technique for sinking flies without weight.

Position yourself as you would for the swing. Cast up and across stream and allow the fly to sink by keeping the rod high and following along with the current as you would in a dead drift presentation. As the line drifts past you, lower your rod at the same speed as the current to continue to allow it to dead drift. When the rod is horizontal, hold it still. Now, the sunken fly will rise to the surface as the current creates drag on the line.

This technique was invented by James Leisenring, a prolific wet fly fishermen around World War II. Many people think the term “lift” means you lift the rod. But it really refers to the “lifting” of the fly by the current (although some anglers do actually lift the rod to accelerate the ascent of the fly). Raising the rod is especially effective in extremely slow water where the current might not be fast enough to create a very enticing “lift.”

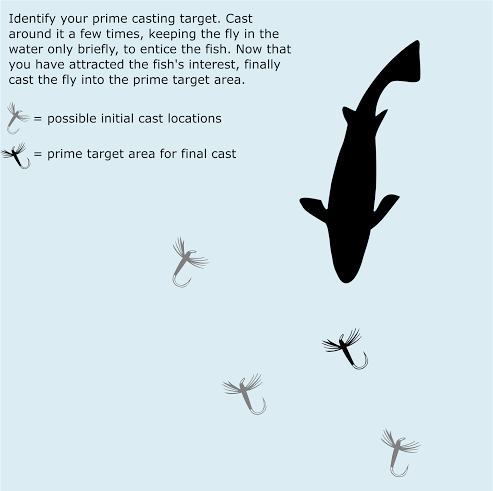

6. Sutebari

Sutebari is a very interesting and unique presentation practiced by tenkara experts in Japan. It might seem a little strange at first but if anglers can catch fish with it on the hard-fished streams of Japan, it would seem to have merit.

The idea here is to “seduce” the fish. Rather than serving up the fly right off the bat, you first present it to them a few times to get them curious and excited.

Identify your prime target (where you think the fish will take the fly). Then, start casting around it a few times, but keep the fly in the water for only a second. Do this a few times and then finally cast the fly right into the prime target. The idea is that even though the fish didn’t have a chance to actually strike the fly before, it got a preview. And now that the fly’s within striking distance, the trout should be enticed enough to take it.

Some delicacy is required here. If you splash the fly down violently and pick it up so fast that it makes a popping sound or a big splash, you could scare the fish off rather than seduce them. Try to make gentle landings and subtle pick-ups.

Sutebari was developed by Japanese tenkara angler Hiromichi Fuji and is just one of many presentations designed to entice fish called “sasoi.” In fact, with the exception of the dead drift, all of the presentations in this article could be considered sasoi.

7. The Pause & Drift

Here’s another unusual presentation from the tenkara world. In this one, you cast across or slightly downstream and follow the drift with your rod as you would with the dead drift presentations. But periodically stop the rod for a second, then resume following the dead drift. Repeat. Drift, pause, drift pause, drift, pause.

What you’re doing is suspending the fly in the water column. Honestly, I have no idea why this presentation works but it does. Perhaps it mimics an insect struggling against the current that has just enough strength to hold itself in one place for a second before giving up (or tiring out) and throwing itself back to the grip of the current. Or maybe it’s just something the fish don’t see very often, and showing them something unusual triggers a strike.

Whatever the reason, like the frequency in the pulsing technique, I don’t think there is any magic formula for how long or how often to pause the fly through a drift. But experimentation will tell you.

8. The Blowline Technique

I first heard about this technique in Gary LaFontaine’s book “Fly Fishing the High Mountain Lakes.” Originally, it was done using a conventional fly rod and reel spooled with dental floss. The idea is to let the wind carry the fly into position rather than casting it. Since dental floss is flat and light, it catches the wind better than heavier plastic fly line. Luckily, most tenkara lines are light enough to use this technique without having to switch to a specialized line—though I would say that lighter #2 to #3 fluorocarbon level lines work best.

Position yourself with the wind at your back or side (depending on where you want to deliver the fly). Raise your rod so that the fly is completely out of the water and the wind catches the line. Move the rod so that your fly is directly above its intended target, then lower the rod so the fly goes into the water.

The blowline technique is a great Plan B in heavy winds where it’s difficult or impossible to cast; however, accuracy can be tricky, especially in erratic, gusty winds. As with anything else, the only way to master it is with practice. So instead of cursing the wind, look at it as an opportunity to practice this technique.

9. Skating the Fly

If you’ve spent a fair amount of time on a stream, you’ve probably seen insects such as caddis skittering along the surface. And you might even have seen a subsequent explosion from beneath the surface from a frenzied trout.

For this technique you can cast upstream, downstream, or cross-stream and as soon as the fly hits the water (or it’s drifted into a position where you think there’s a fish) start quickly “wagging” the rod side to side while you slowly lift the rod, keeping the line tight. This should make the fly skitter toward you while staying on the surface.

While you can do this technique with a traditional sakasa kebari, I find it actually works best with a dry fly such as the elk hair caddis. But my favorite fly for this skating is the Balloon Caddis, designed by Austrian angler Roman Moser. The Balloon caddis has no hackle so it sits a little lower in the surface film. It’s kept afloat by a yellow foam head that makes it very easy to track as it flutters along the surface. That fly was made for skating and I’ve had tremendous success skating it even when there wasn’t a caddis hatch.

10. The Mix Up

It’s been said that the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results. If you’ve fished the same run using one of the presentations above 99 times without any strikes, chances are you’re not going to get one on the 100th try.

Instead, mix it up. Maybe first, try a few dead drifts. If that doesn’t yield any interest try pulsing the fly. Then try a swing, etc. I can’t count the times when I got a strike out a seemingly lifeless pool or run simply by changing technique. Most anglers’ first instinct is to change the fly, and then continue with the same technique. But most tenkara anglers believe the presentation matters more than the fly. So the next time you find yourself futilely flogging the water try switching up the technique rather than the fly. It really does work!

Conclusion

I think one of the main advantages of tenkara is that it allows you to instantly switch between any of these techniques. Whereas with a conventional fly rod and reel switching techniques often means changing flies or re-rigging, in tenkara you can switch back and forth at will without any loss of fishing time. This means you’ll be able to keep your fly in the water more, increasing your chances of catching more fish. Because let’s face it, you’re definitely not going to catch anything while you’re changing tippet size, crimping on split shot, or attaching a strike indicator.

Give a few of these presentations a try. Once you master them, you will have a very effective toolset for adapting to different streamside conditions and convincing stubborn fish to cooperate.